The Caloronutrient Seesaw : How to Succeed Permanently on the Raw-Food Diet

by Dr. Graham

Protein, fat, and carbohydrates are the three "caloronutrients." That is, they are the only nutrients that supply us with calories. On today's standard American diet, people consume an average of 16% of their calories as protein. The remaining 84% is split roughly 50-50 between fats and carbohydrates.

The vegetarians scale back to cheese, eggs, legumes, grains (and often "chicken and fish"), but the relationship of caloronutrients, approximately 42/16/42, generally remains unchanged. This is not surprising, as we tend to gravitate toward the ratio we are accustomed to when we seek to satiate ourselves.

Vegans eliminate the animal fat in foods like dairy, eggs, poultry, and seafood, replacing it with plant fats (oils, avocados, olives, and nuts and seeds). They learn about a wider variety of fruits and vegetables, and read labels to find packaged foods that are animal-free. Still, their caloronutrient ratio tends to remain essentially unchanged.

Raw fooders go one step further. They replace cooked complex carbohydrates with raw simple carbohydrates from fruit. Fruits are more water rich, and hence have less caloric density, than the starchy foods they leave behind. And vegetables, though high in carbohydrates, contain so few calories that they contribute very little to a day's total, regardless of volume consumed.

It takes many more bites to get the same number of calories from fruit's simple carbohydrates than it does from complex ones. So, if anything, new raw fooders raise the percentage of calorie-dense fats in their diets (nuts, seeds, fatty fruits, coconuts, olives, and oils) while reducing the amount of carbohydrates consumed. Some raw-food leaders even recommend the high-fat diet as a successful approach to raw eating. It definitely is not.

A Reduction Is in Order

Nutritionists from every arena agree that we need to decrease our fat consumption from the current one-third to one-half of our calories to less than 20%. With the exception of government recommendations (controlled exclusively by the high-fat meat and dairy industries and bearing no relationship to health whatsoever), the guidelines from wellness-focused professionals are relatively clear and concise: we humans need to consume 10 to 20% of our calories as fat if we seek a healthy outcome.

Why do people find it so difficult to decrease their fat intake to this level? It is because we have been led to believe that complex carbohydrates (starches) are the best carbohydrates for us, that in fact they are the ONLY healthful carbohydrates available. This simply is not so. The much-vilified sweet fruit is your key to a healthy, low-fat vegan diet. We will discuss fruit later in this article, but first I'd like to address a major pitfall of the high-complex-carbohydrate approach.

The problem occurs when we set out to eat our complex carbohydrates without fat and find out that they taste exceptionally bland. When we add fat to make them palatable, we defeat the purpose. When we add processed condiments like sugar, salt, pepper, spices, and artificial flavors, the potential health value of our food tends to deteriorate dramatically.

A diet composed of 30% or more fat has been inextricably linked to most of our major health concerns, including diabetes, candida, chronic fatigue, cancer, heart disease, and many more. We know that excess raw fats are somewhat less harmful than cooked ones, and that overconsumption of plant fats is a lesser evil than the same amount of animal fats. Still, too much fat is too much fat. Like sunshine, exercise, and other foods, fat in excess poses health challenges at least as severe as not enough.

Picture the situation like driving on the highway. Some folks occupy the fast lane. Others drive in the slow lane. But everyone on the highway is headed in the same direction. If too much fat is unhealthy for us, the kind of fat we consume matters far less than the sheer volume of it.

How Much Fat?

So how much fat should we eat? The only fat humans cannot make and need to eat are the essential omega-3 and omega-6s ... and we have no problem getting plenty of the latter. To obtain sufficient omega-3 fat, we need consume only a very small amount of "good" plant-based fat. In 2005, the National Academy of Sciences published its "Adequate Intake" guideline for omega-3 fat, estimating 1.1 grams (for women) and 1.6 grams (for men) to be a safe target (NOT a minimum). This is a fraction of a teaspoon, the equivalent of a couple dozen drops for those who consume oil (a practice I do not recommend). The minimum, it turns out, may be as low as one-fourth that amount.

Broadening the conversation to the more relevant "total fat," we find 5% of calories to be a conservative fat intake that allows for variability among people. And 10% fat, the upper limit I recommend, is at least double what we could conceivably need, even when we allow for inefficient digestion, poor bioavailability, and potential absorption problems. If a diet composed of approximately 10% fat is appropriate, certainly a diet of more than 20% fat is too much fat.

Plant foods, particularly the green leafy vegetables, contain the essential fats we need without our having to think about them. Any diet based around fresh fruits and vegetables that provides sufficient calories to maintain body weight will easily provide the fats we need. All whole plant foods weigh in between 1 and 15% fat ... so if you eat a variety of them every day, and nothing else, your fat needs will be covered quite nicely.

Protein Can't Compensate

When people reduce their fat intake, they often imagine that they can make up the difference by eating more protein. But they are mistaken. The protein content of most of our foods (raw, cooked, animal, or plant) is relatively low. Fruits average in the single digits. Vegetables offer between 10 and 30% protein per calorie on average, but they offer very few calories, as their water density is so high. Most nuts and seeds have a protein content in the low teens, or even single digits (they're mostly fat). And refined fats such as oils offer no protein at all. Neither do refined sugars. Even most animal foods people consume tend to contain one quarter to one half of their calories as protein, with the bulk coming from fat.

Although it comes as a surprise to some, those who take the time to run the numbers with an online nutrition calculator will see that protein content doesn't tend to vary by more than ± 5 percentage points, regardless of diet. Of course, there are exceptions. A diet that is extremely high in refined sugars and refined fats could be low in protein. A diet that relies heavily on refined protein powders in order to raise total protein intake, or one high in specific, specially prepared animal products such as boiled shrimp, roast chicken breast, or tuna packed in water, would show higher protein intakes. Such diets would lead to many other nutrition and health problems, however, as they would be deficient not only in vital soluble fiber but also in a variety of important phytonutrients, antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, and so forth.

If we don't wish to replace our fat with complex carbohydrates, empty-calorie refined sugars, or protein, what then should we eat more of? The luscious answer is fruit.

Making Friends with Fruit

Eating a diet predominated by fruit poses several challenges. Availability is a primary one that is relatively easy to conquer if you are willing to eat with the seasons. In fact, it is exactly because different fruits are available at different times of year that raw fooders get such great nutrition; variety enhances nutritional sufficiency. Also, global shipping has become so available that we can easily obtain fruit year 'round these days.

Fruit quality is another hurdle. To overcome it, we must learn more about fresh fruit than most of us know before considering a high-fruit diet. There are many books and teachers on the subject, and be sure to get to know your greengrocer and local farmers. Choose fruits that are in season, as these will likely be freshest and of the highest quality, and allow them to ripen fully.

Psychology is the next challenge. Most of us do not know anyone who thrives on a diet where fruit predominates; we have no models to follow. The idea feels like treading on thin ice. Yet fruit eating is the oldest of all of our dietary habits. Mankind has thrived on fruit throughout our history. Nutritionally, fruit is supreme. Eating more fruit simply requires recognizing and remembering that no other diet will work as well.

The final challenge is physical. It takes practice to transition to consuming more calories from fruit, as eating fruit requires considerably more volume than eating fats. While a bite of almond butter supplies us with over 100 calories, a bite of most fruits provides about five. So we have to develop a new skill—learning to eat sufficient volume from fruit to remain satisfied until the next meal. We have all experienced the dissatisfaction of eating a fruit meal only to find ourselves hungry an hour later. This is not the fault of the fruit. Any food eaten in insufficient caloric quantity will soon leave us hungry.

Almost anyone who has tried to eat all raw has, on at least a few occasions, found themselves almost uncontrollably eating of cooked foods again. What were the cooked foods they ate? Starches, nearly every time. Why? Because carbohydrates are the preferred fuel for every cell of our bodies; we must get them. If we don't eat enough from simple carbohydrates, we will be coerced into eating complex carbohydrates. Anyone who has ever experienced a craving for something sweet at the end of a meal is getting a message from their body to eat more fruit.

Eating more fat will not lead to a healthy raw-food program, nor will it satisfy our needs for fuel (carbohydrate). Eating substantially more protein is not even an option. As we consume more fruit, our fat consumption will automatically go down. The only healthy way to reduce fat intake is to raise fruit intake.

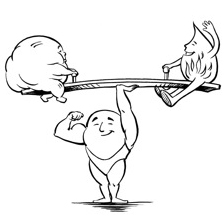

And so we have defined a balanced caloronutrient seesaw. With protein content acting as a fulcrum, hovering around ten percent of calories consumed, we have carbohydrates at one end of the seesaw and fats at the other. For the seesaw to balance, nutritionally, carbohydrates must equal approximately 80% of total calories, and fats 10%. If carbohydrate consumption goes down, fat goes up, and health becomes unbalanced.

A Typical 80% Simple Carbohydrate Day

- Breakfast: All the fruit you care for, usually of a relatively juicy nature.

- Lunch: All the fruit you care for, eating sweeter fruits if they are desired. Consuming celery or lettuce with this meal is optional.

- Dinner: All the acid fruit you care for, followed by a large dinner salad with a small amount of nuts, seeds, or avocado if desired.